During a night of reasoning with Afro-Cuban percussion expert Mike Bennett and singer, historian and native of St. Kitts, Carolyn Smith, I discovered that there is a kernel of truth behind the stories of Zombies in the Caribbean. Nothing to do with the George A. Romero zombies in current popular culture, but something more complex, frightening and real.

Zombification

Zombification Preview

An Available Resources film

At the time I was deepening my studies in Caribbean music, so the thought of telling the Zombie story through music crystallized instantly. I was recommended a book: Passage of Darkness - The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie by Wade Davies. In this book I discovered that not only do zombies exist in Haiti, but most importantly the fear is not of the zombies themselves but of becoming one. Zombification is in fact a punishment - more severe than death - for breaking the common law that exists in rural Haiti.

The numbers of African slaves demanded by the French colonialists in Haiti in the 18th century were so great that the slave traders began to source people from all social groups and from all over the African continent. Traces of language and culture from as far as Madagascar have been discovered in Haitian culture. These educated people brought with them skill sets and knowledge in many ways far superior to that of their captors so it's no surprise that the French were routed in the Haitian revolution of 1791 and that Haiti has been able to resist invasion since.

One of the skills that found its way from Africa in this way was a deep and complex knowledge of poisons - used to startling effect in the revolution. One of the most powerful poisons passed down over generations is that used to Zombify - to turn someone into the living dead. This works in a number of stages and wouldn't work at all unless culturally enhanced through the victim's knowledge of Voudoo - the syncretic belief system of Haiti. Firstly a drug based on the poison of the puffer-fish is given to the victim in powder form. The drug slows down the metabolism to the point that the victim can be certified dead even by western doctors - although chillingly the victim is conscious throughout. He or she then undergoes a full funeral and is buried. By cover of darkness the victim is dug out of the grave by people dressed as the most fearsome of the Voudoo Lwa (saints or gods) - fed an antidote and then an enormous dose of a local hallucinogen - le concombre zombi. If they survive this ordeal they are left in a vegetative state to live a life of hard labour on a hidden plantation.

For Zombification I chose to follow the story of Clairvius Narcisse - who was zombified in Haiti in the 60's but miraculously survived, regained consciousness and rejoined society - with his death certificate still in a filing cabinet in Port-au-Prince.

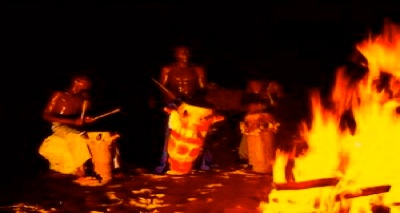

The piece - in fact the entire Horrorshow - begins with the administering of the drug. A powder is blown in to the face of the victim. Not only does the powder contain the active ingredient it also contains plant products that make the skin infuriatingly itchy - and ground glass. As the victim begins to itch and scratch away, the glass abrades the skin and the poison enters the blood stream. Against a background of jungle and sea you hear our victim scratching until he hits a regular rhythm and his journey to a living death begins. Soon the drums of his ancestors and peers join his rhythm. His folk memories and village life leap up in his imagination - but as yet he is unaware of the transformation that is taking place. As his metabolism begins to slow down, so his world effectively accelerates. More images and rhythms from his life appear until a sudden moment of calm. In the distance he hears an African funeral. A child's choir gathers around him and sings a traditional Haitian folk song Nou Pral Mange Zombi (we're going to eat a Zombie), and suddenly, with 3 great doom-laden strikes he realizes what is happening to him. The weight of the ancestral rhythms pour on to him as his metabolism decelerates. His crimes appear before him - the arguments and the threats, the women he beat and the family he stole land from come to him until he acknowledges his death.

His coffin is hammered tight. He is buried - alive.

But then his tormentors appear - one dressed as Baron Samedi, Lwa of graveyards and punishment. He is resuscitated, drugged, whipped and driven off into the night.

Musically I drew on a number of sources, but perhaps the most important is the encyclopedic The Drum and the Hoe by Harold Courlander. All the complex rhythms that drive the piece are derived from the folkloric Haitian music transcribed in Courlander's book. As with most African based culture; rhythms, colour combinations and song denote and bring forth particular spirits - Lwa in Haiti, Orishas in Cuba etc. I chose the rhythms of the most vengeful and cruel spirits to tell the story of Zombification. But as in all complex cultures, vengeance and cruelty can sometimes denote liberation or freedom. The rhythm of resistance.

In the process of researching her profound installation piece Memory and Skin, my friend, photographer Joy Gregory, had spent lots of time researching culture and race in the Caribbean. I asked her if she could contribute some of the recordings she made in her time Haiti to my piece about Zombies. Although we are close friends she was at first reluctant. For her the real horror story of Haiti is not Voudoo, Zombies or Hollywood constructions of African culture as scary and primitive, but simply poverty. Grinding, bitter and cruel poverty has been enforced on Haiti for centuries for having the audacity to become the world's first black republic. I convinced her to allow me to use her recordings by demonstrating 2 things: the depth of the research I'd made to create the piece; and by pointing out one of the precepts of my method - I wanted to make the richest and most complex high quality product using only the resources I had around me, or could borrow, barter or steal. Not only did I play all the percussion in this piece myself, but I made the instruments from what I could find in the street or my garden. The sound world is derived from 1 stolen synthesizer, 2 microphones and piles of old bottle-tops, sticks, axe heads and plastic sheeting. The choir is family and friends gathered around a microphone. I shared sounds I had made with other musicians to get sounds I needed in return. In short the piece cost me nothing, but to make it I had to begin to understand the ingenuity and resilience of the Haitian people.

Of course this is all thrown into sharp relief by the recent earthquake in Haiti and the nature of the world's response. If I have learned anything in the process of making this piece that deserves to be passed on, it is that the cultural treasure-trove of the Haitian people is so great and so resilient that they will emerge from this most recent horror, on top of the previous generations of horrors before them, stronger and more ingenious then ever.